CAPS is a combined effort by Federal and State agricultural organizations to conduct surveillance, detection, and monitoring of agricultural crop, and forest pests. Survey targets may include insects, nematodes, plant diseases, weeds, and other invertebrate organisms. In Tennessee, the CAPS program is coordinated from within the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Invasive pests are of serious concern for Tennessee’s agriculture, forestry, and wildlife. Many educational resources are available from UT Extension, Protect Tennessee Forests, Tennessee Invasive Plant Council, and Hungrypests.com focused on protecting our native species.

What’s New

Exotic species on the move!

Insects

Origin and Distribution: The Asian longhorned beetle (ALB; Anoplophora glabripennis) is a federally quarantined wood-boring insect that inflicts severe damage on trees in North America. It is native to China and Korea. Although it has not been found in Tennessee, ALB was first identified in the U.S. in 1996, likely brought over multiple times in wood packaging materials from its native regions. Presently, populations of this beetle exist in only four states, all of which have active quarantine zones with ongoing eradication efforts. The beetles are often unintentionally transported to new areas in cut firewood or wood packaging material.

Description and Life Cycle: Adult ALB have a shiny black body with white spots on their backs. They are large beetles (¾ – 1 ½ in) with white and black banded antennae that extend much longer than the length of their body. ALB Larvae are cream-colored, legless, and roughly 2 inches long at their latest larval stages. Adult beetles emerge in spring or early summer, escaping trees through round exit holes. Female ALB chew small depressions into the bark of a tree to lay their eggs. In about two weeks, the larvae hatch and bore into the tree. ALB pupate within the tree and emerge several weeks later as an adult.

Damage and Impact: ALB damages trees by tunneling through the sapwood and heartwood of trees or branches, disrupting the flow of nutrients and water. This larval tunneling significantly weakens the tree, making infested trees potentially hazardous. Additionally, tunneling in the sapwood disrupts the tree’s ability to transport water and nutrients, leading to the tree’s death within 7 to 9 years. Since no treatment is known for infested trees, removing them is essential to reduce hazards and prevent the pest’s spread to new areas. The most effective methods to safeguard Tennessee forests from this pest include avoiding the movement of untreated firewood, early detection, and eradication efforts.

Photo courtesy of Michael Bohne, U.S. Forest Service, Bugwood.org

Origin and Distribution: The Asian needle ant (Brachyponera chinensis) is an invasive species native to China, Japan, and Korea. It was first discovered in the United States in the early 1930s but has been recognized as a pest since 2006. In the eastern U.S., these ants have established populations in several states, including Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee Virginia, and Wisconsin.

Description and Life Cycle: Asian needle ants are medium-to-small in size with a relatively long and slender body. They are dark brown to black in color, with lighter brown to orange-brown antennae, legs, mouthparts, and stinger. The worker ants are typically 4-5 mm (0.2 inch) in length, while the queen may measure about 6.5 mm (0.25 inch). They have a prominent stinger that protrudes from the rear abdomen when in use. The Asian needle ant has a complete life cycle comprising egg, larval, pupal, and adult stages. Adult males and females develop wings, aiding their flight away from the nest in mating swarms during the summer. Their nests are often found in moist, damp areas such as inside rotting logs, leaf litter, beneath rocks, and in loose soil. It is not unusual to find nests around sprinkler systems and inside pavement crevices.

Damage and Impact: Asian needle ants can displace native ant species and other insects and impact key ecosystem functions, such as seed dispersal. Their venomous sting can cause allergic reactions in some individuals, posing a health threat.

Photo courtesy of Mohammed El Damir, Bugwood.org

Origin and Distribution: The box tree moth, originating from East Asia, has become a significant invasive pest in Europe, where its spread continues. The caterpillars primarily feed on boxwood, and severe infestations can defoliate these plants. After the leaves are consumed, the larvae attack the bark, leading to girdling and eventual plant death.

Description and Life Cycle: Adult box tree moths are white with a brown head and abdomen. Wings are white with an irregular thick brown to black border (1.6 – 1.8 in wide). Eggs of the box tree moth are pale yellow (0.04 in). Females lay eggs singly or in clusters of 5 to over 20 in a gelatinous mass on the underside of boxwood leaves, with most females producing over 42 egg masses during their lifetime. These eggs typically hatch within 4 to 6 days. Pupae usually first appear in April or May and remain present throughout the summer and into the fall, depending on the local climate and generation timing. Adults from the overwintering generation emerge between April and July, depending on climate and temperature, with subsequent generations active from June to October. After emerging, adults typically live for about two weeks.

Damage and Impact: Box tree moths are highly mobile and capable fliers. In Europe, the natural spread of this moth is approximately 3 to 6 miles per year with the possibility for adults to fly over 20 miles. Box tree moth larvae feed on the leaves and the bark of boxwood plants. The younger larvae feed on the undersides of leaves, removing the color and giving the leaves a paper-like appearance. Maturing larvae will feed on entire leaves, leaving behind only the midrib. As the plant is defoliated, the larvae will move to feed on the bark, girdling and possibly killing the plant. Later stage larvae also produce noticeable webbing.

Photo courtesy of the U.S. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service

Origin and Distribution: The brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB), Halyomorpha halys, is an invasive species from Asia. BMSB was first identified in the United States from Allentown, Pennsylvania in 1998, but experts suspect it was present since 1996. It was later documented in Knox County, Tennessee in 2008, and is now well established in Tennessee. Only a few counties in West Tennessee have not yet documented this pest.

Description and Life Cycle: Adult BMSB measure about 1 inch in length and ¾ inch in width. Adult BMSB have a mottled coloration of various browns or light pinks/purples and can be distinguished from other stink bugs, such as the native brown stink bug, dusky stink bug, and spined soldier bug, by the alternating white bands on the last two segments of their antennae and the alternating dark and light bands along the edge of their abdomen. Similar banding is also found on the legs of the nymphs. BMSB undergo five nymphal stages (instars). The first instars are orange and black, staying near the egg mass after hatching. From the second to the fifth instar, they are dark brown with some beige and purple coloration, growing larger with each molt. BMSB eggs are typically laid on various surfaces, often found on the underside of leaves, with an average of 28 eggs per mass. In our region, BMSB typically produce two generations per year. After the second generation, adults overwinter in sheltered areas, including homes and other structures, and then resume their life cycle the following spring.

Damage and Impact: BMSB invade homes and structures during the winter but cause no structural damage. Limited evidence indicates that people with allergic reactions to cockroaches and lady bugs may have similar reactions to BMSB due to an airborne allergen that it emits. To most people, BMSB are primarily unwanted nuisance pests in the home due to their large numbers and the unpleasant odor released when disturbed. However, BMSB is also a severe agricultural pest, with a wide host range that damages many of Tennessee’s important crops, such as tomatoes, okra, beans, peppers, soybeans, sweet corn and, most notoriously, and apples. In addition to row crops, fruit trees, and vegetables, BMSB may damage many common ornamental plants. Both the adults and nymphs cause injury by feeding on developing seed or fruits with their piercing-sucking mouthparts.

Photo courtesy of JMohammed El Damir, Bugwood.org

Origin and Distribution: The cotton seed bug (Oxycarenus hyalinipennis) is widely distributed in the Caribbean, including the Bahamas and Cuba, and is also found in Africa, Europe, and South America. Although present in the West Indies since the early 1990s, it was first recorded in Puerto Rico in January 2010. By March 2010, it was detected in the Florida Keys and in the U.S. Virgin Islands by April of 2010.

Description and Life Cycle: The eggs are oval and less than 1 millimeter in size. The pest undergoes incomplete metamorphosis with five nymphal instars, which have pink to red abdomens. Development from egg to adult can be completed in 20 days, with three to four generations per year. The last generation undergoes an inactive, dormant phase. Populations of the pest have been found in crevices in tree trunks, telephone poles, or wooden posts, undersides of tree leaves, pods of legumes, dried flower heads, grass roots, under sheath leaves of corn and sugarcane, and on the leaves of mango, guava, and citrus plants.

Damage and Impact: Both adults and nymphs feed on seeds, sucking oil from mature seeds. Host plants include cotton, okra, kenaf, apricot, peaches, and grapes. The lack of competition from related species, coupled with abundant suitable hosts in the United States, increases the risk factor for this pest.

Photo courtesy of C. Mares, CSIRO; https://www.uaex.uada.edu

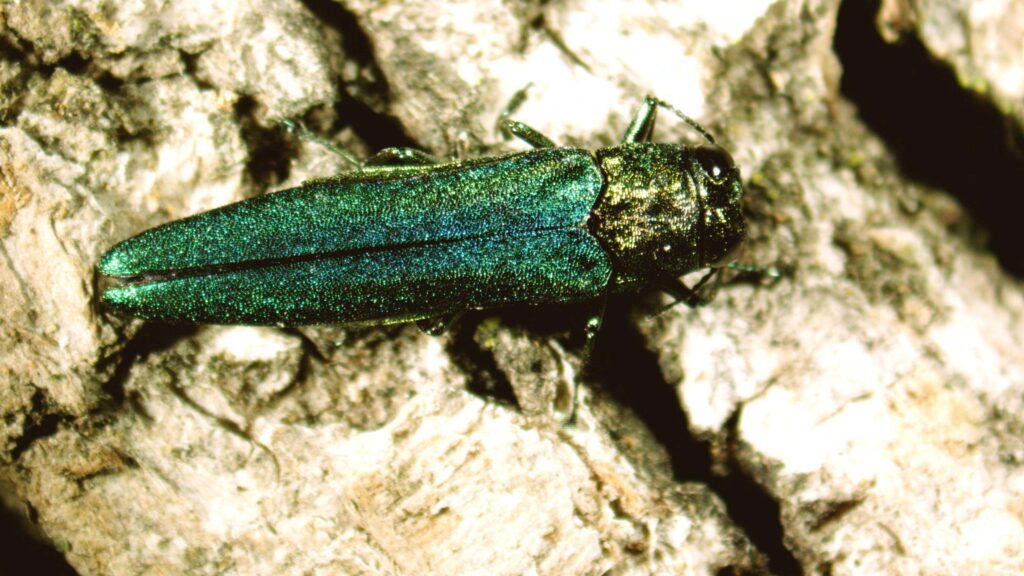

Origin and Distribution: The emerald ash borer (EAB; Agrilus planipennis), a beetle native to Asia, was first identified in North America in Michigan in 2002. Since then, it has caused significant damage and death to ash trees (Fraxinus spp.) across 35 states. In Tennessee, EAB was first found in 2010 at a truck stop on I-40 in Knox County. Since then, it has spread to at least 65 counties in the state.

Description and Life Cycle: Adult EAB are an iridescent metallic green color. They are between 3/8- and 1/2-inch long and 1/16-inch wide. Due to their size, they can often go undetected, but they can be seen on ash bark and leaves during warmer months. Adult beetles emerge from infested ash trees by creating a D-shaped exit hole that is about 1/8″ wide. Most beetles disperse less than 1/2 mile from their original location. Eggs are very small (1 mm), difficult to find and are rarely seen. Female beetles deposit 40-200 eggs in bark crevices and as larvae hatch from the egg, they immediately chew their way into the tree that hatch in about two weeks. Larvae are cream-colored and slightly flattened, with a pair of brown pincher-like appendages on the last segment. Their size varies as they feed and grow under the ash tree’s bark. Fully grown, they average about 1.5 inches in length. Larvae tunnel and feed in the nutritious tissue beneath the bark. They wind back and forth as they feed, creating S-shaped patterns called galleries under the bark. The larval stage is the most destructive because their feeding behavior disrupts the flow of nutrients through the tree. They feed under the bark for 1–2 years and can survive in green wood, such as firewood, if the bark is still attached. After one or two years of feeding under the bark, larvae will create a chamber for themselves in the wood beneath the bark.

Damage and Impact: All ash tree species are susceptible, and there is no management method once EAB has attacked a tree other than tree removal. EAB adults feed on leaves in the canopy, and larvae feed in the phloem, girdling and killing the tree. Adults make D-shaped holes as they exit the trunk. EAB infested trees often show thinning or yellowing crowns, sprouts growing from the lower trunk and roots, and woodpecker damage (as the birds go after larvae). Several chemical methods are available as preventative measures, especially for high-value trees. Biological control options are being evaluated, but the most effective management strategy appears to be limiting the human-induced movement of larvae, which can be transported in logs after dead ash trees are turned into firewood. The primary means of spreading this pest is human activity, particularly through the movement of infested nursery stock, firewood, unprocessed saw logs, and other ash-related materials. Although it was subject to quarantine upon its discovery in the United States, both state and federal restrictions were removed in 2021 after federal deregulation of the beetle.

Photo courtesy of the U.S. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service

Origin and Distribution: European grapevine moth (Lobesia botrana) was first detected in the United States in California in 2009. This pest was fully eradicated from the United States in 2016, but monitoring continues due to it’s significant role as a pest and the constant chance for reintroduction to the U.S.

Description and Life Cycle: European grapevine moth has two to four generations per year and is active from early spring to late summer. The moth overwinters as a pupa at various locations such as under leaf litter, in the soil and under grapevine bark. Adults feed on nectar. Adults have a 5-7 mm wingspan with cream-white color forewings with gray, black, and brown markings. Male hindwings are white while female hindwings are dark gray. Larvae can be up to 10 mm long with a yellowish-green to grayish-green body. Eggs are lentil-shaped, 1 mm long, and initially

yellowish in color, but later turn gray. Eggs are are laid on stems and berries.

Damage and Impact: European grapevine moth is a significant pest of berries and berry-like fruits. It feeds on the flower or fruit of host plants, most often grapes. The moth is a significant agricultural pest throughout much of the world. The first generation of larvae feed on flower clusters, while later generations feed inside the fruits. Webbing, excrement, and fungal infections as a result of larval feeding can damage the whole bunch of grapes or berries.

Photo courtesy of Jack Kelly Clark, Regents of the University of California

Origin and Distribution: The hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae), or HWA, is native to Asia. First reported in the U.S. in 1951 near Richmond, Virginia, HWA has since spread to 21 states, ranging from Maine to Alabama. Since its detection in Tennessee in 2002, HWA has spread to 43 counties in East Tennessee and the Cumberland Plateau, advancing from east to west at an average rate of 15 to 20 miles per year.

Description and Life Cycle: HWA is small (1/32 inch) and “aphid-like” in appearance. It has a reddish-purple body which it covers with a white, fluffy secretion, making them appear “woolly”. HWA overwinters as females within fluffy masses. They begin laying eggs in February. Flat, naked, reddish-brown adelgid crawlers hatch from the eggs and move about actively. Once the crawlers settle, they become black with a white fringe around the edge and down the center of the back. Young adelgids live on twigs or at the bases of old needles. Adelgids are parthenogenic and only females are known. Most of the nymphs develop into wingless females that lay eggs in a fluffy mass on hemlock.

Damage and Impact: HWA suck sap from young hemlock twigs, preventing tree growth and also cause needles to turn grayish-green, and drop prematurely. The loss of new shoots and needles is highly detrimental to a tree’s health. An infested tree usually defoliates and dies within a few years. This insect poses a serious threat to the health and sustainability of eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) and Carolina hemlock (Tsuga caroliniana) in the Eastern United States. HWA is considered the greatest single threat to hemlock health in the eastern U.S., with potential ecological impacts comparable to those of Dutch elm disease and chestnut blight. The primary vectors for the rapid spread of HWA are storm winds, migratory birds, and “hitchhiking” on mammals and humans. Infested nursery stock can also introduce the insect to new areas. While hemlock is not highly valued as a timber species, it provides critical ecological benefits, such as habitat, stream temperature regulation, and stream bank stability. The loss of these benefits would disrupt delicate forest ecosystems and negatively affect aesthetic and recreational values. Due to the near-microscopic size of HWA crawlers (mobile instar phase) and their ease of transport by birds, mammals, and weather, traps are not effective for monitoring infestation movement across the state. However, traps are used in research settings to detect presence and spread rates. For detecting new infestations or assessing hemlock health, visual inspection of hemlock trees remains the most effective survey method. Several agencies have established annual survey locations to record infestation presence, hemlock tree health, and other relevant data.

Photo courtesy of U.S. Forest Service

Origin and Distribution: The red imported fire ant (RIFA), Solenopsis invicta Buren, the black imported fire ant (BIFA), Solenopsis richteri Forel, and their hybrid (often all collectively abbreviated as IFA) are nuisance insects native to South America specifically in the areas of northern Argentina, Uruguay, Peru, and southern Brazil. Both species were introduced into the United States at Mobile, Alabama in 1918 (BIFA) and the 1930’s (BIFA). IFA spread rapidly through the southeastern U.S. during the 1940’s and 1950’s. The hybrid IFA was first described in the U.S. in 1985. Some combination of the two species of IFA and their hybrid are presently found in 18 states. They spread naturally during their mating flights. This spread is usually one mile or less but flights of up to 12 miles have been recorded. Ants can also float downstream in masses or on debris during floods.

Description and Life Cycle: The quickest to identify an ant colony as IFA is by observing the colony’s immediate and aggressive behavior when the nest is disturbed. New colonies of IFA are formed by one (or more) winged, mated females (queens) following a mating flight. The mated queens find suitable nesting sites, shed their wings, and begin digging underground chambers to lay their eggs. The first eggs and larvae are cared for by the queen. They emerge as small workers after three to four weeks. Thereafter, workers care for the queen and the brood, forage for food, and expand the nest. An undisturbed colony can increase in size rapidly and may contain 10,000 or more workers after one year. Winged reproductives will also be produced sometime in the second half of the first year. A mature colony (3 years old) may contain 100,000 to 500,000 workers and several hundred winged forms. Mating flights occur most commonly in spring or early summer, one or two days after a rain when the weather is warm and sunny and the wind is light.

Damage and Impact: IFA stings can cause serious medical problems for humans and animals. Imported fire ants interfere with outdoor activities and harm wildlife and livestock throughout the southern United States. Ant mounds are unsightly and may reduce land values. In some cases, imported fire ants are considered to be beneficial because they prey upon other arthropod pests. In urban areas, fire ants prey on flea larvae, chinch bugs, cockroach eggs, ticks and other pests. In many infested areas, the problems outweigh the benefits and controlling fire ants is highly desirable. However, eradication of this species is not currently feasible. When deciding whether or not to control fire ants, one must weigh the benefits of fire ant control against the cost and environmental impact of control methods. Consideration of biological control of fire ants may not be compatible with some types of insecticide use. Insecticides are not always 100 percent effective, nor are most approved for use everywhere that ants occur. Insecticides are also expensive and potentially hazardous to the environment and other animals. Chemicals provide only temporary control of fire ants and must be reapplied periodically. Where applicable, you should select programs (for urban or agricultural areas) that use a combination of non-chemical and chemical methods that are effective, economical and least harmful to the environment. For more information regarding fire ants in Tennessee, visit UTIA’s fire ants page to learn more.

Photo courtesy of the U.S. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service

Origin and Distribution: The Old World bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) is a significant agricultural pest. It is native to Africa, Asia, Australia, and Europe. It was first discovered in Brazil in 2012 and is now also present in South America and the Caribbean. In 2014, the pest was found in Puerto Rico, and in 2015, specimens were captured in Florida. In 2019, APHIS detected adults in areas adjacent to Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport and is eradicating the isolated population.

Description and Life Cycle: The life stages of the Old World bollworm are almost identical to those of the native corn earworm (Helicoverpa zea), and both species feed on the same plants. Only a trained professional can distinguish between the two species. Adult moths have a wingspan of about 1.4 inches and vary in color from light yellow to greenish brown to orangish brown. Fully developed larvae can be up to 2 inches long and can range in color from bluish green to brownish red.

Damage and Impact: Old World bollworm is extremely damaging to over 180 plant species, including corn, cotton, small grains, soybeans, peppers, and tomatoes. While adult moths are strong fliers, it is the larvae (caterpillars) that cause substantial damage by boring into the flowers and fruits of plants and feeding inside. Damage by larvae can include holes bored into the base of flower buds, fruit, or bolls, feeding damage to leaves and shoots, causing young fruit or bolls that fall prematurely, and internal feeding damage to fruit.

Photo courtesy of Gyorgy Csoka, Hungary Forest Research Institute, Bugwood.org

Origin and Distribution: The redbay ambrosia beetle (RAB) (Xyleborus glabratus) was first detected in the United States in Georgia in 2002, likely through imported wood packing materials from Asia. Since then, is has spread across the southeastern U.S.

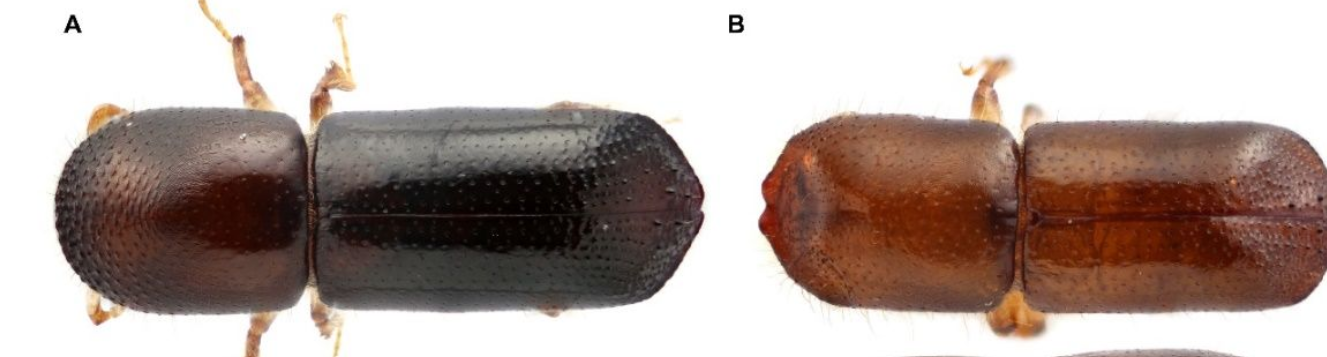

Description and Life Cycle: The beetle is rusty brown and very small. Adult females measure around 3 mm, while males are smaller, measuring around 1.5 mm. The larvae are white, c-shaped, legless grubs with an amber-colored head capsule. Adult female beetles bore into the wood, lay their eggs, and create tunnels (or galleries) which spread the fungus throughout the tree. The beetles then use the fungus as a food source. It takes about 55 days to complete one generation in Tennessee.

Damage and Impact: This wood-boring beetle is a primary vector for the fungal pathogen Harringtonia lauricola, the causative agent of laurel wilt (LW) disease that impacts plants within the family Lauraceae. Sassafras (Sassafras albidum) and northern spicebush (Lindera benzoin) are the only host plants for this beetle in Tennessee. Trees infested with RAB show symptoms such as small “toothpicks” of sawdust (ejected wood fiber from beetle boring) sticking out of their trunks at the point of attack. Tree foliage appears reddish or purplish and begin to droop or “wilt”, with sections of the crown or the entire crown eventually turning brown. There are currently no available methods to save a plant once infected with LW. The beetle, together with LW can wipe out entire stands of lauraceous plants.

A) adult female and B) adult male ambrosia beetle.

Photo courtesy of Andrew J. Johnson, UF/IFAS

Origin and Distribution: The spongy moth (formerly known as the “gypsy moth”; Lymantria dispar dispar) is a nonnative moth responsible for defoliating over 95 million acres of hardwood forests in the northeastern United States over the past century. Native to Europe and northern Africa, it was introduced to Massachusetts in 1869. Since then, it has spread southward through the northeastern states into southwestern Virginia, with a major front advancing toward Tennessee at approximately four miles per year. The spongy moth’s range now covers 19 states.Currently, there are no established spongy moth populations in Tennessee. Although isolated spongy moths have been detected in Tennessee annually since the statewide trapping program began in the 1970s, none have developed into established populations. Each year, Tennessee places traps to monitor spongy moth detections. When a positive identification is made, an extensive pattern of traps is installed around that location. These traps help the Tennessee Department of Agriculture determine the source, extent, and direction of a potential infestation. Often, infestations can be eradicated through extensive trapping, but sometimes spray operations are necessary. The success of the extensive trapping and treatments conducted over the past 50 years has prevented the establishment of spongy moth populations in Tennessee.

Description and Life Cycle: The name “spongy” refers to the spongy-like appearance of the egg masses with 500-600 eggs. Eggs are laid in August. They overwinter as eggs and hatch in mid-May. Newly hatched larvae are about 1/4 inch (6.3mm) long. To move to better sources of food, the larvae often produce silken threads that catch in the wind and send them aloft to other trees (ballooning) which allows them to spread farther. Early instar larvae are small, dark brown-to-black, and very fuzzy. Later instars lighten in color and have a showy display of two rows of colored spots: five pairs of blue and six pairs of red. At about seven weeks, larvae are fully grown at 2-2 and 1/4 inches long (50-56 mm) and pupate. Once they complete pupation, adult male spongy moths, which are brownish with black markings and a wingspan of 1 to 1 1/4 inches (25-32mm) emerge and fly erratically during the daytime in search of mates. Females are white with brown markings that resemble an inverted V pointing toward the head. They are heavy-bodied with wings but don’t fly. They rest on trees and wait as males follow female pheromone trails to find them.

Damage and Impact: Spongy moth causes significant defoliation of trees in many areas. While small-scale defoliation events rarely result in permanent damage to trees, large-scale outbreaks can cover thousands of acres and recur over multiple years, weakening trees over consecutive seasons. These forests, weakened by repeated defoliation, become more susceptible to various pests, pathogens, and abiotic stressors that can lead to tree mortality. The damage caused by the spongy moth has had substantial economic impacts throughout the northeastern U.S.

Photo courtesy of Milan Pernek, Forestry Research Institute, Bugwood.org

Weeds

Kudzu, Pueraria montana var. lobata (Willd.) Maes. & S. Almeida, often referred to as the “vine that ate the South,” is an invasive plant known for its rapid growth and widespread presence in the southeastern United States. Originally from Japan, kudzu was marketed as an ornamental plant and ground cover to stabilize soil, but it quickly spread beyond its intended areas. Due to its extensive planting and rapid growth, many states have been managing kudzu for over seventy years. This invasive plant has now also spread to parts of the Midwest and northeastern U.S.

Kudzu’s rapid growth and ability to blanket trees and structures in a thick layer of vines have raised concerns for forested areas and old field sites. It often prevents native plants and trees from establishing, creating a monoculture that reduces species biodiversity and diminishes the ecological and economic value of affected areas.

Kudzu primarily spreads through vegetative runners, where nodes that touch the ground can establish roots and expand. While it can grow over a foot a day, there are management options available to control small areas of kudzu and prevent the vines from spreading.

Photo courtesy of James H. Miller, U.S. Forest Service

Mile-a-minute weed primarily self-pollinates. This plant produces fruits and viable seeds without the need for pollinators. The vines typically die with the first frost, but the weed is a prolific seeder, producing numerous seeds from June to October in Virginia, with a slightly shorter season in northern regions. Seeds can persist in the soil for up to six years, with staggered germination.

Birds are likely the primary agents for the long-distance dispersal of mile-a-minute weed. Utility rights-of-way, such as powerlines, provide important dispersal corridors. Seeds can also be transported short distances by at least one ant species, which may aid in the survival and germination of seeds, though further investigation is needed. The seeds have an elaiosome (a nutritious food body) that may attract ants. Local bird populations help disperse seeds under utility lines, bird feeders, fence lines, and other perching locations. Other animals observed eating the fruits include chipmunks, squirrels, and deer, with viable seeds found in deer scat.

Water plays a significant role in dispersing mile-a-minute weed. Its fruits can remain buoyant for 7 to 9 days, enabling long-distance dispersal in streams and rivers. Fruits from long vines overhanging waterways are easily carried away by water currents. Storm events increase the likelihood of seed spread throughout watersheds.

Photo courtesy of Britt Slattery, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Plant Pathogens

First discovered in 2002, laurel wilt has rapidly emerged as a serious disease in the southeastern U.S. Caused by the fungus Harringtonia lauricola, laurel wilt can kill mature trees very quickly. The primary vector of the fungus is the redbay ambrosia beetle (Xyleborus glabratus), a small beetle from Asia, although several other insect species can also spread the fungus. This disease affects plants in the Lauraceae family, most commonly targeting redbay in coastal areas where it was first discovered. In Tennessee, it primarily impacts sassafras and spicebush.

Laurel wilt is of significant concern due to its ecological impacts on coastal redbay groves and its potential economic impact on avocado crops in Florida, which are also susceptible. The disease was detected in Tennessee in 2019 on sassafras and has since spread to 23 counties.

More information can be found on our laurel wilt factsheet.

Photo courtesy of Ronald F. Billings, Texas A&M Forest Service, Bugwood.org

Soybean rust (SBR), caused by the fungus Phakopsora pachyrhizi, is a disease that, like other rusts, can only survive on living tissue for extended periods. The fungus overwinters in the southeastern U.S., with spores traveling to the upper Midsouth each year to initiate infection. Symptoms of SBR can closely resemble those of other diseases such as Septoria brown spot and bacterial pustule. However, distinguishing features can be observed with a 30x hand lens or dissecting microscope.

SBR is characterized by raised, pimple-like structures called uredinia or pustules, which resemble small volcanoes. These structures develop in angular lesions, primarily on the underside of leaves, and release spores through a circular central opening, which is diagnostic. In contrast, Septoria brown spot lesions are flat, and bacterial pustule lesions have irregular, cracked openings. SBR symptoms first appear on leaves in the center and lower canopy.

Photo courtesy of Melvin Newman – Emeritus, University of Tennessee

First discovered in 1995, sudden oak death has become a significant problem in northern California and Oregon. The pathogen, Phytophthora ramorum, is currently killing tanoaks, coast live oaks, and California black oaks in these western states and poses a threat to the extensive oak forests of the eastern United States. Despite its name, “sudden oak death” is somewhat misleading, as trees often succumb to the disease over several years. The disease causes severe girdling cankers on the main stem and large branches of the affected trees.

Phytophthora ramorum is known to infect hundreds of plant species, most of which do not display obvious symptoms. This asymptomatic infection increases the risk of the pathogen being introduced to new areas via infected landscape plants shipped from nurseries in the Pacific Northwest. Although this disease is not established in Tennessee, the Tennessee Department of Agriculture conducts annual surveys to monitor for the pathogen and prevent its accidental introduction.

Photo courtesy of Bruce Moltzan, U.S. Forest Service, Bugwood.org

In 2010, the discovery of a disease affecting black walnut trees in Knox County, TN, raised significant concerns for Tennessee’s forest industry. Thousand Cankers Disease (TCD), caused by the fungus Geosmithia morbida, led to walnut tree mortality and spread to several neighboring counties. Walnut trees are highly valued for their nut production and their wood, which is prized for lumber and veneer. While recent years have seen fewer detections of the disease, the following information details TCD, its impact in Tennessee, and the recent lifting of the state quarantine for TCD.

TCD is a progressive disease known to kill walnut trees within two to three years of initial infection. However, some trees with milder infections have shown the ability to recover. The walnut twig beetle (WTB), Pityophthorus juglandis, carries the spores of G. morbida and tunnels into the trunks or branches of black walnuts. The combined activity of the fungus and beetle results in the development of cankers, and repeated attacks can eventually lead to tree mortality. The walnut twig beetle is native to Arizona, California, and New Mexico and has more recently been detected in Colorado, Oregon, Idaho, and Washington. While the native origin of TCD is unknown, the disease has been present in the western states since the late 1990s.

Photo courtesy of Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org